Should We Mine the Ocean?

- Josh Robertson

- Feb 15, 2021

- 23 min read

Updated: Jun 11, 2021

The world needs more metals for a sustainable future. However, extractive industries and conservation fit together like orange juice and toothpaste! So, I was obviously sceptical when I heard companies were trying to mine the deep ocean – what conservationist wouldn't be?! But is ocean mining better than mining tropical rainforests? I spoke with world ocean expert Dr Greg Stone to find out.

Metal mined from the deep sea

Josh: "Hi Greg, thanks for meeting with me today - let’s get started!

Can you please tell everyone who you are and what you do please, Greg?"

Greg: “Yeah, my name’s Greg Stone and I’m an oceanographer. I’ve studied the ocean all my life and I've had a diverse career. Currently, I work for Deep Green as their Chief Ocean Scientist and I'm on their board of directors. Before that, I was the Chief Ocean Scientist for Conservation International, a big NGO. And before that I was on the World Economic Forum, National Geographic Society and sort of did a lot of things. But at the moment this project with Deep Green is my priority... it's a very exciting company."

Josh: “What was it about oceans that drew you to them?

Greg: "Well, I grew up outside of Boston, my family didn’t have anything to do with the ocean, we were inland. But I started watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries as a kid and man, those got me. I'd count the days between episodes. I'd sit on the floor with my mask and flippers and watch it. Then I finally got to the ocean when I was about 7 or 8 and dove into it with my cousin - we each had flippers and just fell in love with it from that day forward."

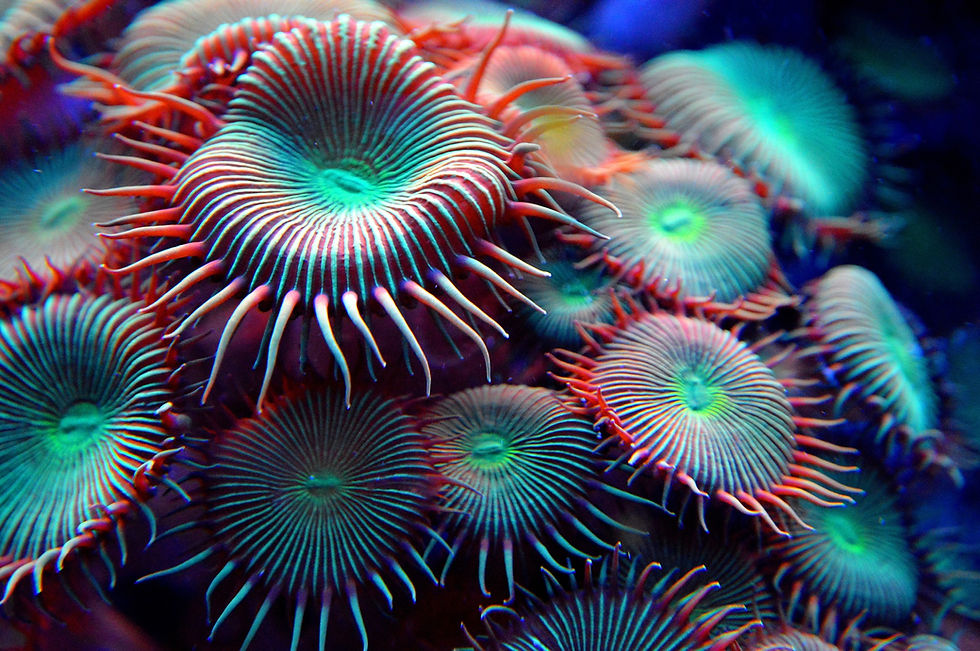

📸 Tomas Kotouc

Josh: “What's your life's mission?"

Gregg: "My life mission is to find ways for modern society and the ocean to support each other on a sustainable basis. In other words, we get things from the ocean and then we have to in return support the ocean - it's got to be a relationship that is balanced and our lives depend on getting that right.

Buckminster Fuller famously called it 'spaceship Earth' and that was the best metaphor ever. We're never gonna get resupplied, everything we've ever had is here, everything we ever will have is here. The thing that Buckminster Fuller said that everybody forgets is 'the only problem is, spaceship Earth didn't come with a manual'. And I'd like to help work on writing the manual.

... We've had several industrial revolutions which change things... the next revolution is what the World Economic Forum calls The Fourth Industrial Revolution: it's about renewable energy, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, machine learning, and big data – that's the next wave.

That's really what the work I'm doing today is centred around: finding the best way to supply the key materials for this fourth revolution, mostly metals, with the lightest environmental and social impact on a planetary scale – and we know how to do it, that's the beauty of it!

What is frustrating and challenging is we don't have the political will and the public awareness to get it right...

I've been in ocean conservation since 1990, and during the 90s we were trying to figure out the problem... which by 2000 was well understood to be a combination of habitat loss, climate change, overfishing, invasive species, and pollution. We then developed a toolkit of policies and technologies to better manage and protect the healthy functions of the ocean; now it's just a question of applying the tools to the problems at a planetary scale, and that is really hard. I spend a lot of time thinking about what has inspired big change in the past... it's never science or an argument, it's a person who's inspirational, it's an idea or religion, it's different things. We need something now to change... and maybe it's your podcast."

Josh: "Haha wouldn't that be great?! Okay, so who is Deep Green?"

Greg: "Deep Green is a metals company and has an important role in enabling the decarbonisation of our society in the fourth industrial revolution.

We've got to change our energy systems. It's more dangerous than you think, what's going on right now. We are warming this planet up so fast. I'm terrified at what might happen... The change is okay, everything always changes. It's the speed at which it changes that's the problem. It's like we're driving down a windy road on the edge of a steep cliff with a speed limit of 30 km an hour, but we're driving at 100 km an hour... it's so dangerous!

We're already having violent weather conditions. You think global warming sounds nice, it does to some people 'Ohh it's going to get warmer'.

It's more like global chaos: that's a much better word for it. As you energise the earth's atmosphere, water, and land with heat, it causes unpredictability and chaos

A big problem is ice, Josh. Think about the poles. Ever since there's been hominids on the planet... we've had very, very established icy poles and the ice does two things: reflects light and heat back out into space and it makes the ocean circulate. A circulating ocean is what brings us all the benefits that we like: oxygen, fish, and all these other benefits.

📸 Tomas Kotouc

Now as you lose the ice, what is it replaced by? It's replaced by a dark surface – water. So you lose a highly reflective surface and it's replaced by a dark surface that only intensifies the warming. When you lose an ice cap it doesn't come back in 100 years; it doesn’t come back in 1,000 years; we're talking about 100,000 or million year cycles to get icy poles back. And every time you read a story in the news they say 'the ice is melting faster than scientific models predicted' they always say that it's worse than expected because we have insufficient data on the condition of the ocean. It's like a doctor trying to diagnose a patient by looking at them through binoculars. So, I really worry about our ability to sense and diagnose the condition of the ocean before it's too late.

📸 Charles Kinsey

I've worked in Antarctica, I've dived down there and I know that environment. And we can hit a tipping point where we can't stop it. We can stop it now, if we really focus. Everybody has to focus. It has to be like a war: like WW2. For your grandparents and my mother and father in the US, it's all they thought about everyday... and they overcame it!"

Josh: "So, how are Deep Green helping the situation?"

Greg: "There are certain things that we've needed from the Earth in the past, that we can't make ourselves. These are the extractive industries. There was a time when burning wood was the only way that we could make heat, but then we figured out we can burn some other things, like oil, coal, and natural gas. We now need to stop burning oil and start making electricity, heat, and motion by capturing the mechanical/kinetic energy of wind and water, and the electromagnetic energy of the sun. Then we have to store it because our world operates on electricity that we can turn on and off when we like.

This next revolution consists of devices that require metal and batteries to store electricity – but we can't make metal. The atoms that metal is made of can only be made in stars. We have not mastered the energies involved (in making metals) yet; elemental atoms can only be manufactured by nature.

So, we have to take those metals from the earth in order to transform ourselves to a renewable energy world.

We need a lot more metal. In fact, it's looks like 500-1000% more, depending on the metal; things like nickel, cobalt, manganese, copper, etc. Electric car batteries are like a third of the weight of the whole car. There may be 1.5 billion cars on the planet by 2050, and we hope to have a billion of them electrified to reduce emissions. Those car batteries must be charged by electricity generated from renewable sources, otherwise we'll still be emitting pollution into the atmosphere.

That's a key point – it's not driving an electric car that's good for the planet, it's charging the batter with renewable, non-polluting energy sources; something that's not burning fossil fuels.

So, where are we gonna get this metal?

Most likely we take it out of the ground, because that's where we live. We're terrestrial creatures by nature and we've dug it up in the past. But mining is the dirtiest industry on the planet: it produces 25% of all the solid waste, and 15-18% of all the CO2 humans put in the atmosphere. The wonder of metals is the atoms are infinitely recyclable, so once we have enough metal in use, we can close the loop of the economies of the metal industry and use it over and over again. We should also lower demand, like does everybody have to have a car?

But, even with severe cutbacks, we still need a big influx of virgin ore to have the long sought after closed loop economy (an economic system that reengages waste products into resources).

So, the question is where to get this metal that will cause the last harm to the planet. If we get this from the land, it's going to mean digging up more and more tropical rainforest, where Nickel Laterite deposits are found and, coincidentally, most of these are found in the highest biodiversity areas on the planet, like Indonesia. Additionally, lots of people in these places are significantly impacted by terrestrial mining, particularly if a tailings dam breaks. There's a lot of waste in terrestrial ores – up to 97% – but there's no waste in the option I'd like to discuss.

In the ocean there are these potato-sized rocks called manganese polymetallic nodules, which form on the ocean floor like a pearl. They aggregate atoms of these metals slowly over time and take around 7 million years to form.

Manganese polymetallic nodule

And they sit there, around 4-5 km down on the surface of the seafloor in vast plains of abyssal muds with mostly worms, sea cucumbers, microbes, and other invertebrates. The biodiversity is an order of magnitude less than on land, and there are no plants, mammals, or people down there – it's so remote, dark, and cold. Then there's this one area in the central Pacific, thousands of miles offshore, where they are very dense and they contain exactly the metals that we need for batteries.

It's almost remarkable that this exists.

It's in an area about 1% of the seafloor and its regulated by the United Nations through the International Seabed Authority. The policy to develop and regulate this industry has been in development for a few decades, although they were first discovered in the 1860s by your country: the UK sent a ship around the world and dragged up samples here and there and they found these nodules with a very high ore content for certain base metals like nickel, copper, cobalt, and manganese. On land, if you want these same 4 metals you need 4 mines. But they're all in these nodules together: you never have a co-occurrence of these metals in one place [on land].

And they just sit on the seafloor, they're not attached to anything. You just pick them up and bring them to the surface; they have zero waste. On land, often you're only using 2-3% of the mountain that you take apart to get the metal. In this case, every little piece is used. There is some residual material that's not a metal, but it can be used in concrete, it's benign, like silica. So when I say no waste, I mean there's nothing toxic and it all has a use.

You look at a metal mine on land, you end up with all kinds of horrible substances that cause birth defects and make people sick. When you add on the collapse of tailing dams, it's all a very dangerous industry on land.

And there's this option: a new option. People are resisting it because it sounds horrible; deep sea mining sounds bad. But think about what it is. It's picking up highly concentrated ores of battery metals on the seafloor that are sitting there. That doesn't sound so bad.

Is there going to be some ecological disturbance on the seabed? Yes. Is there going to be more disturbance to the seabed than there is to a tropical rainforest? No... It's a trade-off.

If you could get the metal out of the air or you could make it, or if there's another alternative that somebody could put in front of me, I'll do that instead... I'll quit this job and do that instead. This is the best option.

It's very counterintuitive to have somebody like me supporting this, because my whole life's been around ocean conservation. I did that intentionally to get people's attention, because I wanted to use whatever reputation and trust that I had in this sector, to let people know that this is what we should do.

I probably love the animals down there more than most people do. We're talking about worms, nematodes and polychaete worms, they're all invertebrate animals. If I showed you a picture of the bottom of the ocean, it's nothing: a very muddy just flat area. It's not like a coral reef, there's not a lot of stuff there. You mostly see these rocks, and then an animal here and there.

We have to do 3 years of an Environmental Impact Assessment before we can apply for an exploitation permit.

I've talked to a lot of my colleagues about it, oceanographers, and I've said 'what do you think?' Everybody, well not everybody, but most of them feel that when you look at the planetary system, again you've got to dial it out and think about the spaceship and not think about what's happening in this one area, but what's good for the planet. This is the best option in front of us. And if anybody has a better option, contact me and let me know."

Josh: "So how exactly do you extract these incredibly rich nodules from the seabed?"

Greg: "It's like a vacuum cleaner or like a combine harvester on the seafloor, where this tractor goes along and it'll have a hydraulic suction system in the front and it'll pick the nodules up and then they'll go to the surface in what’s called an air rise, which is just a pipe about 1 m across. You push compressed air down the pipe and it causes a very strong upward flow and we're trying to design it to leave most the sediment at the bottom; the fine sediment that settles on the seafloor. So, when the nodules get to the surface, you could imagine a pipe and then pouring out of the pipe is mostly rocks and the sediment stays below.

Then we return the water through another pipe, back to an appropriate depth so that it produces minimal interference with the biology of the ocean, because it's different water, it's much colder and has these different chemical properties."

We're trying to isolate the activity from the surface and it's not that hard to do. You just have a return pipe that will go to a depth that will cause minimal disturbance, and that is partly what our research right now is about –learning as much as we can to make these design decisions.

It's the first time in the history of industrial activity on the planet that we've had the opportunity to apply a precautionary reproach, to really think about it ahead of time and plan.

Usually you're looking over your shoulder when starting to drill for oil or something else and you can try to correct and make the right decisions after.

They actually did it in the 1970s. Lockheed Martin went out there and spent about a billion dollars and found it viable. But we didn’t have an international agreement on how ownership rights would be handled. Now we have an international agreement over how this is done and importantly there's a profit-sharing clause in this that says there'll be an off-take of profits that goes back to the developing world countries that don't have the capital to do this on their own.

To me, is it perfect? No. But, it tries to take on as many lessons learned, to do with socio-economic equity and ecology, over the last couple of years and apply them as best we can for this activity. And we'll get better at it as we do more of it."

Josh: “You've essentially got like a gold mine on the ocean floor, where you're taking a giant hoover and hoovering everything up. There's going to be lots of competition for claims to these seabeds.

Do you think there's the correct legislation in place or is this going to be an increasingly important geopolitical issue, where lots of companies see what you're doing, copy you, and then the deep seas are plundered all over the world?"

Greg: “Well, the United Nations passed the Laws of the Sea, which is kind of like the constitution for the oceans. It covers this issue in quite the detail, so it's not it's not a wild west out there.

You've got to go through a lot of procedures and the UN actually has to vote on every permit. So after we spend a lot of money over the next three years, we have to describe the oceans baseline conditions out there and have to do collector tests: where we hoover up some of the rocks and look at the kind of plume that generates and then we extrapolate that out into a commercial scale and we report what it would do to the ocean and whether that’s an acceptable disruption to the ocean system. "

Josh: “I read a report by Flora and Fauna International and it was an assessment of the risks and impacts of seabed mining and marine ecosystems. It talked about the controversy and uncertainty about the methods of deep seabed mining and I'm just going to quote one of the things that they said: 'none of the technology is being developed to achieve no serious harm to the environment and decades of investment in seabed mining concepts has resulted in the development of machines and processes that may be highly impactful'.

How are deep green ensuring that their extraction methods will not be highly impactful?"

Greg: “Well, we have the unique opportunity to have a co-evolution going on here, where we do environmental impact assessment studies now, it's basically classic oceanography, and then we have the engineering house working on the system, and we have a dialogue going back and forth. We're telling them: the water has got to be returned at this depth, it's better if we can leave bigger nodules behind to provide habitat for animals called obligate species, so we're perhaps trying to design in some inefficiency so there's habitat left behind.

So, we haven't gone there yet, this is a process, and it's a big process. The time to make that kind of claim is 2-3 years from now, when we've done the research and spent the money and we make the case, and we lay it out before Flora and Fauna International and the world, and say this is what we intend to do and these are the benefits and these are the negatives - what do you think? That's the time when resistance should be launched; I think some of this is very premature. It's not acknowledging the fact that this has been in development for decades. It's a process and we're at the beginning of this process.

If they if they don't want mining to occur, they should wait and see what the science says. We don't have the science yet: we're investing in that science now.

Josh: “I guess people are worried that companies will just go in and plunder it without doing these sorts of assessments. I think that is a huge concern if you just went straight in and no one knew about the impacts, then I think that's completely understandable."

Greg: “I wouldn't want that either! That's when you get back to the fourth industrial revolution; we need to bring in artificial intelligence and lower cost monitoring of the deep sea - we can do that now. These problems can all be solved and again, if there are critics who don't want this to happen, give me an alternative. I don't accept don't do it. That doesn't work for me, they have to give me an alternative.

The metal you have in your computer right now, and what I have around me, came from probably a very dirty mine from the other side of the world, in a developing country. If you had that mine in your backyard, you'd probably feel a little differently about this. I mean, if you see the brutality of it. We're so insulated in the developed world from what happens."

Josh: "Do you not think that we can recycle what we have to meet the future demands? Would it not be more environmentally friendly to continue to work on our untapped recycling potential?"

Greg: “I wish we could; I really wish we could. If there was enough metal around, I would go that route. But there just isn't. To give you some examples: offshore windmills, you know the big gigantic windmills? You need 15 tons of manganese for each windmill, and manganese is not one of those metals that's just everywhere.

But, there's a lot of it in these nodules. People don't realise the scale of the demand. Then you have to put that against the time pressure we have to cool the planet down. I'm not saying we should just recklessly do something to cool the planet down; no. I'm saying that we should go by the science and I believe the science that I can see in front of me right now, it's in a report that you probably had access to, it speaks pretty clearly to me and we're only going to add more to that over the next three years, and it's urgent. It's really urgent that we solve this. We don't have 20 years just to sit around and think about it. And there just isn't enough metal around."

Josh: “Okay, good to know. Let's just go over the main environmental concerns associated with mining these deep sea nodules."

Greg: "Sure. I can describe it to you: you're gonna have a tractor on the sea floor that's gonna drive along at a slow pace and its gonna suck the nodules up.

There's not a lot of fish down there, I've spent a lot of time in the deep sea in submarines, I know what it's like, I've got a feel for it. There's not a lot of energy in the deep sea, it's a very cold, slow, strange place. There's no day, there's no night. Things grow very slowly and the fish that are down there are very strange creatures that look like the guy who used to hide under my bed when I was 12 years old.

But forget about them. What we're talking about is the animals that live in the mud and on the mud, and those are worms, polychaete worms, nematodes, bacteria, viruses etc. Those are the animals that we're talking about.

Some of them will get crushed as the vehicle goes across, some of them will go through the system and then out the back, some will get caught and die. Some will die. There is no question about that.

But, we have a policy where, within our blocks of lease sites, 75,000 km2 blocks, we set aside areas that we call reference zones: essentially, similar areas to where we mine so that we make sure that there are areas left that are undisturbed and have the same kinds of animals there. So, that's our general mitigation strategy. And, as we do this study, we're going to know more about what the impacts are. We will try to avoid all that we can, and for the ones that we can't avoid, we're going to try to minimise them. It will come down to choices.

Let's put aside climate change for a second and just look at biodiversity.

It'll come down to people having to decide what they value more: do they value orangutans in the jungles of Indonesia or do they value a little worm about that long (about an inch) with segments in it, that doesn't even have a face?

📸 Simone Sbaraglia

And we don't want this job, I mean the world not Deep Green: the world doesn't want to be the adjudicators of this. But it really comes down to this: the alternative is disrupting high biodiversity areas on land, where we disturb what we would probably consider animals that are much closer to us on the scale of evolution, closer to conscious beings, you know, like an orangutan. Those are the choices.

The other thing is, there's a deeper line to this Josh that people don't often get to. The hard-line position of some of the critics saying 'don't do it, we don't need all these metals anyway, let's change the way we live' - they're all sitting in comfortable homes in the developed world and living life like I do. They're not living in an underdeveloped country where the average life expectancy is 55.

The resistance to this has a knock-on effect to the development of these other countries. We owe it to the world to give everyone, I think, the same opportunities that we enjoy: healthcare and education. That comes with the infrastructure of society that you are I are living in. That's a deeper level of this. It's complicated, it's very complicated, but it's there.

You're not going to find one critic from the developing world taking these positions that you're reading about here.

Then there's some concern over ecosystem service. I'm sure you know what they are, but for your listeners, ecosystem services are benefits that people get from nature: like oxygen, freshwater, things like that.

During our study, we've looked at the ecosystem services provided by the deep-sea to people, and we couldn't find any on any meaningful timescale.

Now, we may disturb the water chemistry a little bit down there and one thousand years from now that water may come back to the surface and be a little bit different. We haven't done the equations to show it, but we couldn't find a connection. There's nothing down there that directly related to humanity. So, we're really talking about existential value of creatures. And these are creatures I happen to be very fond of.

I'm probably fonder of these creatures than the people that wrote that report (FFI). I've seen them, I've been down there, I love the deep sea and I'm willing to put all that out on the line to try to get people to make a rationale, science-based decision here.

I don't blame them, there's not a lot of great history in industry, especially extractive industries. In the past they say 'Ohh don't worry about it, we're gonna take care of it' and they didn't. Once burned, twice cautious."

📸 African penguin covered in oil from oil spill off the coast of South Africa - Martin Harvey

I'd be interested to know how they tried to come up with a value for ecosystem services in the deep oceans and came up with nothing – I find that quite questionable and it would be interesting to hear your opinion on that with all your experience and knowledge?"

Greg: “Yeah, are you familiar with the Ocean Health Index? "

Josh: “No, I'm not."

Greg: “Have a look at that. It's a tool that I co-founded that divides them up into categories, the benefits that we get from the ocean. We pretty much used those categories. We don't get food from down there, we did the calculations on the carbon disruption, whether there would be any released carbon from the deep sea from this activity, and we had one of the top people in the world on this issue do the calculus: two-three pages of calculus. He said it's going to be insignificant. He certainly doesn't like mining though, he doesn't like the idea. He said I don't support it for other reasons, but he said you don't have to worry about carbon; that's an ecosystem service, absorbing carbon and storing it.

So there's no impact there. There's no food impact, we just can't find a connection. There's a value impact. People are allowed to have a value system that values these worms and that's what it's about. They have to realise it's a trade-off. It's not the worms on their own, it's the worms or this. That's where people really have to look at the big picture, the planetary view."

📸 NASA: Apollo 17 Earthrise

Josh: “I guess looking at the big picture, the ocean is obviously all completely connected, the deep sea remains our least explored, largest environment on the planet. We know more about space than we do about the deep sea.

How can you predict the impacts in the zones that are perhaps unknown?"

Greg: “Yeah, well, we do it through working with the best experts in the world that we can find that understand and study these systems. We've contracted them to do the work. We're doing the environmental impact assessment quite differently from most companies; most companies will go to another consulting company and have them do all the work, but instead we went out to the academic community and set up contracts with scientists all over the world: actually, some of them have stood up and been critical of the industry. But we want them because we know their science is pure. They may have opinions but they're not gonna let their opinions leek into their science.

You have to remember 70% of the planet is ocean and we live on the other 30%. If we go back to the spaceship Earth model, you know where do you really want to be getting your supplies? From under the house you live or from the ocean where you don't live? Do you want to be impacting animals like tigers and orangutans and tropical rainforests where people live, where you may have to displace indigenous people and on top of that concentrate toxins? Terrestrial mining concentrates toxins, whereas nodules are made so fundamentally differently, there are no toxic by-products.

The case will be made with science, with this 3 year study I helped design and support. Its unprecedented in the history of extractive industries to have this much work done before extraction begins. You know, if you want to put it an oil rig out somewhere the environmental impact assessment takes like 6-weeks, and then they make a hole and drill. We'll spend 3 years of studies before a decision is made to go forward or not - a very precautionary approach.

I put the challenge out there, we are addressing those issues in our research plan, so the results will be there, but if someone knows something I don't then tell me! I know a lot about the ocean and I just can't see it. We're spending a lot of money to codify and document this with some of the world's top scientists. "

Josh: “So where exactly will you be mining? If you could just remind us of how big the area is and where exactly in the world it is?"

Greg: “Well, first of all, the area that has these nodules with the right composition – the Clarion Clipperton Fracture Zone – is 1,000 miles west of Mexico and is 4.5 million km2. It's part of the abyssal plains in the ocean: the largest habitat on the planet, and the whole area set for nodule mining is 1% of the global seafloor. The policy of the ISA is to set aside half of this area as reference zones as a precaution."

Josh: “Can you just describe what reference zones are for the audience?"

Greg: “It's like a protected area, where you don't mine that area. It's part of the precautionary approach that we've learned over the last several decades. In the absence of knowledge, you do the most precautionary thing you can think of; in this case, it would be to set aside areas.

We're also going to be taking samples of the bacteria, the microorganisms periodically and freezing them for prosperity, so that as we go along, if there's the remote possibility that there's a highly localised organism we don't know about, there will be reference samples. That's really never been done before in the history of any industrial activity. We're really going beyond as far as we can, taking every measure we can think of to ensure that this is taken care of."

Josh: "So, we've seen with lots of resource extraction that they can be very negative for the environment and for people, which we've spoken about, but we also know how important transparency is, not in the industry but across the supply chain. I was just wondering how Deep Green are ensuring this transparency?"

Greg: “Yeah, we have internal discussions and policies around it and we try for our comms and business development to have radical transparency. If you go to our website you'll see pictures and videos of what's going on the boat right now, we have a boat at sea at the moment. We try to be active and open in the social media space, answering questions and seeking opportunities like this to talk to you.

I think that if this all goes forward, as I think it will, that the international Seabed Authority is going to need some vehicles of some sort where they could come up to a boat unannounced and send a vehicle down to the bottom and make sure that what's happening is what's supposed to happen. That's becoming increasingly less expensive as technology goes forward.

We're trying to make everything we do available. If there's something more you think we can do or your listeners think we can do, let me know and I'll make sure we do it."

Josh: “Okay I just have one last question and it's because I saw this as a quote in the report I read from Flora and Fauna International. I'll just read you the quote, it's from a very wise man:

'The fate of the deep sea and the fate of our planet are intimately intertwined. That we should be considering the destruction of these places and the multitude of species that they support, before we have even understood them and the role they play in our planet, is beyond reason'. So how would you respond here to Sir David Attenborough?

Greg: “Well, as I said my own ideology is that the fate of the ocean and the fate of humanity are the same, which is similar to what he said. The reason it sounds like we differ is because I'm looking at the entire Earth/Ocean/Atmospheric system as a whole, everything is connected, and the projected planetary damage from increased terrestrial mining is worse than what will happen to the deep sea, We are also in the middle of an expansive 3-year research program for our Environmental Impact Assessment, which will make the region less unknown.

Civilisation is in the middle of a major course correction because of climate change. We need energy systems that do not pollute our atmosphere, and this requires an influx of new materials, especially battery materials, that can only come from the earth itself. Turns out that new science shows picking up loose lying rocks (polymetallic nodules) from the seafloor is far less destructive to the planet than terrestrial mining. He's isolating what's happening in one place and looking at just that. He's a very brilliant man.

Did you read the response that we sent him about that? I think we can share that with you, we wrote a letter to Sir David – a very respectful letter. I have a great amount of personal admiration for him. We responded to him. I basically agree with him. To answer your question, I actually agree with him. I agree we should choose the path that is least destructive, which is essentially what he is saying. From the data that I've seen, that sources polymetallic nodules on the seafloor."

Josh: “So you agree with him that it's damaging, but what you're doing is the best of what we have?"

En realidad, el casino es una fuente de ingresos dudosa, pero no estoy de acuerdo. He estado jugando al proveedor de casino online mr bet durante mucho tiempo y no puedo decir nada malo sobre él. Según las estadísticas, este casino online tiene el RTP más alto.

The mobile app design by Digi Glume exceeded my expectations. It’s not only visually appealing but also highly functional, offering a great user experience. The team was responsive and professional throughout the process.

The custom web development services did an outstanding job creating our website. Their creativity and technical skills are truly commendable.

It's an annoying experience that could interfere with how you stream media.

The excessive CPU utilisation of Plex Media Scanner could be caused by big libraries, ineffective settings, antiquated hardware, transcoding requirements, or out-of-date software. Hardware improvements, setting adjustments, and library optimisation are some of the solutions.

It seems that emirulewd is not an accepted term in the English language. It might be an inventive use of language, a typo, or a term unique to a particular environment or specialty.